Train heads back up the charts

Published in Berkshire Eagle, 8/7/11

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

LENOX—The members of San Francisco-based band Train already knew how to be rock stars. But they had to hit a wall, deal with commercial disappointment and face the prospect of dissolution before emerging, eventually, with their biggest success yet.

The band, known for its friendly pop hooks and big, radio-ready choruses, comes to Tanglewood on Tuesday, full of momentum from fifth album "Save Me, San Francisco," whose title track recently became the record's fourth charting single. Boston Cello Quartet, comprised of four young members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, will open with a set to include two specially prepared arrangements of Train songs.

Currently riding high and in the midst of a well-received, co-headlining tour with Maroon 5, Train stands only a few years removed from its nadir, a time when the band seemed as likely to break up as to continue. (Tuesday’s concert does not include Maroon 5.) After its 2006 album "For Me, It's You" failed to chart a single, the band went on a three-year hiatus during which its future was in doubt.

"I don't even know if we would still be band if we wouldn't have taken that break," recalls guitarist Jimmy Stafford in a telephone interview from Charlotte, North Caroline the afternoon of a show. "We took a break just to get away from it all. We knew it didn't feel right. After a few years we decided: we love this band, let's get our band back. And to do that we need to get rid of a bunch of the people that are unbalancing the chemistry."

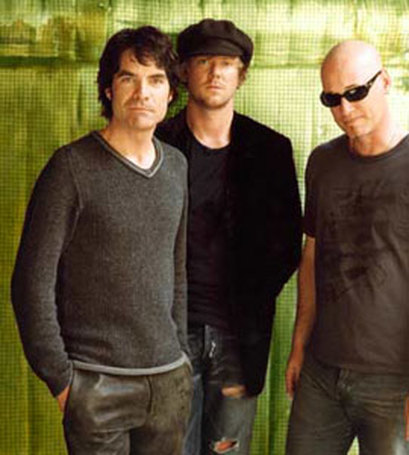

As a band wedded to the traditional major-label system, living (or dieing) on the strength of pop hits and exposed to the vagaries of music-market trends, the band needed to come up with another hit. The rebuilding process included finding new management and firing two band members, returning to the founding trio of Stafford, drummer Scott Underwood and lead vocalist Patrick Monahan.

But the way back was not smooth: the first sessions for the new album were halted when things didn't seem to be working out with its original producer. And even after its release, "Save Me, San Francisco" dropped off the charts before the smash single "Hey, Soul Sister" emerged out of nowhere and rescesutated the band. That song went on to win the Grammy for best pop performance by a duo or group, as well as the Billboard Music Awards' nod for top rock artist and the ASCAP Pop Music Awards recognition for song of the year.

In sum, it returned the band to commercial heights it hadn't seen since the heady days when its power ballad "Drops of Jupiter (Tell Me)" was ubiquitous on modern rock radio, capturing five Grammy nominations in 2002 and winning two.

LENOX—The members of San Francisco-based band Train already knew how to be rock stars. But they had to hit a wall, deal with commercial disappointment and face the prospect of dissolution before emerging, eventually, with their biggest success yet.

The band, known for its friendly pop hooks and big, radio-ready choruses, comes to Tanglewood on Tuesday, full of momentum from fifth album "Save Me, San Francisco," whose title track recently became the record's fourth charting single. Boston Cello Quartet, comprised of four young members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, will open with a set to include two specially prepared arrangements of Train songs.

Currently riding high and in the midst of a well-received, co-headlining tour with Maroon 5, Train stands only a few years removed from its nadir, a time when the band seemed as likely to break up as to continue. (Tuesday’s concert does not include Maroon 5.) After its 2006 album "For Me, It's You" failed to chart a single, the band went on a three-year hiatus during which its future was in doubt.

"I don't even know if we would still be band if we wouldn't have taken that break," recalls guitarist Jimmy Stafford in a telephone interview from Charlotte, North Caroline the afternoon of a show. "We took a break just to get away from it all. We knew it didn't feel right. After a few years we decided: we love this band, let's get our band back. And to do that we need to get rid of a bunch of the people that are unbalancing the chemistry."

As a band wedded to the traditional major-label system, living (or dieing) on the strength of pop hits and exposed to the vagaries of music-market trends, the band needed to come up with another hit. The rebuilding process included finding new management and firing two band members, returning to the founding trio of Stafford, drummer Scott Underwood and lead vocalist Patrick Monahan.

But the way back was not smooth: the first sessions for the new album were halted when things didn't seem to be working out with its original producer. And even after its release, "Save Me, San Francisco" dropped off the charts before the smash single "Hey, Soul Sister" emerged out of nowhere and rescesutated the band. That song went on to win the Grammy for best pop performance by a duo or group, as well as the Billboard Music Awards' nod for top rock artist and the ASCAP Pop Music Awards recognition for song of the year.

In sum, it returned the band to commercial heights it hadn't seen since the heady days when its power ballad "Drops of Jupiter (Tell Me)" was ubiquitous on modern rock radio, capturing five Grammy nominations in 2002 and winning two.

One change from previous practice on the new album was the recruitment of outside collaborators to participate in the songwriting. Stafford attributes that to the fact there were fewer band members around this time. "We weren't trying to write hits. We were just trying to put together a record that we loved. When we did that, ironically we ended up with some hits," he asserts. "Listeners are smart. I think they sense sincerity and when a band is being genuine or disingenuous. I think this album came from the heart and just came from the right place, and I think people sensed it and they took to it."

Stafford says the band’s earlier successes made it self-conscious, leading it away from the commercially savvy instincts that marked its first few albums.

“[At first] we just wrote music and we were fortunate enough to have a few songs from those early albums played on the radio. And then we kind of got away from that and we started trying to write those songs again,” he reveals. “Success feels good. You work so hard to finally get somewhere and you get there and you want to maintain it. I think we got preoccupied for a few years with trying to maintain the success, as opposed to just being ourselves and letting it happen the way that it should.”

Now, after enjoying its return to the limelight, Train faces a familiar problem—though a good one to have.

“We've had a bigger success than we've ever had in our careers now, and we have to be careful with this next album we're currently writing, to not fall back in that same trap,” he says.

Selected to open the concert with its blend of four cellos, the Boston Cello Quartet was charged with compiling a program that would appeal to Train fans. One straightforward solution presented itself: member Blaise Déjardin wrote arrangements for Train favorites “Marry Me” and “Parachute.”

“I wanted a song that was a bit more rich and interesting, harmony-wise. I picked ‘Parachutes,’ which is a pretty lush score for a pop song,” Déjardin, who interpreted the songs by ear, explains. “’Marry Me’ is more of the simple guitar style, but there were some interesting things I could do with the accompaniment of four cellos.”

Stafford says the band’s earlier successes made it self-conscious, leading it away from the commercially savvy instincts that marked its first few albums.

“[At first] we just wrote music and we were fortunate enough to have a few songs from those early albums played on the radio. And then we kind of got away from that and we started trying to write those songs again,” he reveals. “Success feels good. You work so hard to finally get somewhere and you get there and you want to maintain it. I think we got preoccupied for a few years with trying to maintain the success, as opposed to just being ourselves and letting it happen the way that it should.”

Now, after enjoying its return to the limelight, Train faces a familiar problem—though a good one to have.

“We've had a bigger success than we've ever had in our careers now, and we have to be careful with this next album we're currently writing, to not fall back in that same trap,” he says.

Selected to open the concert with its blend of four cellos, the Boston Cello Quartet was charged with compiling a program that would appeal to Train fans. One straightforward solution presented itself: member Blaise Déjardin wrote arrangements for Train favorites “Marry Me” and “Parachute.”

“I wanted a song that was a bit more rich and interesting, harmony-wise. I picked ‘Parachutes,’ which is a pretty lush score for a pop song,” Déjardin, who interpreted the songs by ear, explains. “’Marry Me’ is more of the simple guitar style, but there were some interesting things I could do with the accompaniment of four cellos.”