Stillness of winter via music

Published in Berkshire Eagle (2/27/09)

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

PITTSFIELD—“It burns as only ice can burn,” French poet Charles Baudelaire once wrote, referring to a novel.

I think I know the feeling.

There’s a certain chilly joy to be had in The Low Anthem’s mysterious, beautiful album, “Oh My God, Charlie Darwin.” For all its snow-swept ruminations on dislocation and disintegration, and the lingering storm cloud of some crucial but elusive American riddle hovering above, there’s a wholeness at its center—even if one stitched together with disappointed, purse-lipped Yankee resilience—that in the end is a kind of comforting.

The Low Anthem plays Mission Bar and Tapas on North Street Monday, on the heels of the September release of “…Charlie Darwin,” the band’s second, self-released album.

If ever an album sounded reflective of its recording environment, it’s this one. The band and a small cadre of friends and collaborators sent all the necessary gear for a temporary recording studio off to Block Island, Rhode Island on a ferry; on New Year’s Day of 2008 they started an intense ten days of recording, in the basement of an abandoned summer home.

The album’s liner notes describe the circumstances as “the ghostly stillness of a Block Island winter.”

It sounds it.

“We liked the idea of going out there, especially with this body of material, because the environment suits the album. We were out there on this island, isolated... in a sort of utopian community with our closest friends, and I think the album is hopeful for all of that,” says Ben Knox Miller, primary singer and lyricist, during a phone call from Brooklyn. “The songs certainly have a longing in them, but it’s also very bleak, and maybe ultimately it’s not so optimistic.”

Weirdly, the album feels at times like a rootsy, acoustic update of the dirge-rock sound pioneered by Slint’s 1991 masterpiece “Spiderland.”

Published in Berkshire Eagle (2/27/09)

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

PITTSFIELD—“It burns as only ice can burn,” French poet Charles Baudelaire once wrote, referring to a novel.

I think I know the feeling.

There’s a certain chilly joy to be had in The Low Anthem’s mysterious, beautiful album, “Oh My God, Charlie Darwin.” For all its snow-swept ruminations on dislocation and disintegration, and the lingering storm cloud of some crucial but elusive American riddle hovering above, there’s a wholeness at its center—even if one stitched together with disappointed, purse-lipped Yankee resilience—that in the end is a kind of comforting.

The Low Anthem plays Mission Bar and Tapas on North Street Monday, on the heels of the September release of “…Charlie Darwin,” the band’s second, self-released album.

If ever an album sounded reflective of its recording environment, it’s this one. The band and a small cadre of friends and collaborators sent all the necessary gear for a temporary recording studio off to Block Island, Rhode Island on a ferry; on New Year’s Day of 2008 they started an intense ten days of recording, in the basement of an abandoned summer home.

The album’s liner notes describe the circumstances as “the ghostly stillness of a Block Island winter.”

It sounds it.

“We liked the idea of going out there, especially with this body of material, because the environment suits the album. We were out there on this island, isolated... in a sort of utopian community with our closest friends, and I think the album is hopeful for all of that,” says Ben Knox Miller, primary singer and lyricist, during a phone call from Brooklyn. “The songs certainly have a longing in them, but it’s also very bleak, and maybe ultimately it’s not so optimistic.”

Weirdly, the album feels at times like a rootsy, acoustic update of the dirge-rock sound pioneered by Slint’s 1991 masterpiece “Spiderland.”

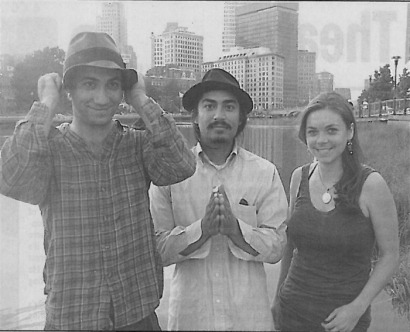

Courtesy photo

The Low Anthem is a band not long for Pittsfield bars. This Providence-based trio is featured as a “breaking” act in the March 5 issue of Rolling Stone; the piece declares it “one of the East Coast’s hottest unsigned acts.” It recently played NPR’s “World Café” program, and is on the bill of the ginormous Bonnaroo Festival in June.

In 2008 it netted the “Best New Act” distinction from the Boston Music Awards, and topped the “Best Album” poll in The (Providence) Phoenix.

Knox and Jeff Prystowsky started the group in 2006 after first meeting as Brown undergrads, and they’ve self-released one album a year since. Jocie Adams played clarinet on one track of the 2007 record “What The Crow Brings,” and was added as a full-fledged member in time for “…Charlie Darwin.” They’re all multi-instrumentalists, and work through various combinations of musical tools both in the studio and on stage. The new album features 27 instruments, including an “ancient” pump organ (Knox’s term), banjo, acoustic guitars, clarinet, cello, harmonica, and various forms of percussion.

“We play musical chairs in our rehearsal space and just try every different permutation of instruments, until the frequencies get excited and we know we're onto something that moves us,” Knox explains. “And when it stops moving us, then we just go back to the drawing board and try different arrangements again.”

He says they bring about a dozen different instruments out for any given show.

After spending nine months tinkering with debut “Crow” in a home studio, the band set out to record the follow-up in one “blitz” in that house on Block Island, Knox says.

“It was about ten days straight of no sleep, and it was very tense at times, but our technique for recording was to do twenty to twenty-five takes of each song, back to back, and just kind of exhaust ourselves into coming up with something.”

He says they tried 60 takes of album opener “Charlie Darwin” before they “stumbled up to” the arrangement featured on the album.

On the whole, the end effect ranges from icy, acoustic beauty (see “Charlie Darwin,” featuring falsetto vocals from Knox), to a rowdy, junkyard clamor evocative of Tom Waits. (The album’s one cover is “Home I’ll Never Be,” Tom Waits’ musical adaptation of a Jack Kerouc poem, for which Knox apparently sucked on sandpaper and assumed an entirely different vocal identity.)

In short, it’s Americana, but a timeless variety that also feels curiously placeless. With the notable exception of railroad blues “To Ohio” and the Waits/Kerouac composition, there are almost no place names on the album, nor any clear historical references. In spots, it feels like there are stretches of frostbitten prairie, an ominously inflamed horizon (stared at from a moving train), and, at the opening of the album, a terrifying expanse of cold water all around. In the mystical workingman’s-lament-cum-love-song “Ticket Taker,” the narrator sells tickets for safe passage on an “arc” and confides he “keep[s] a stock of weapons, should society collapse.”

When asked in what time and place he sees these songs unfolding, Knox pauses to consider.

“There's nothing modern about the vocabulary, and yet a lot of the scenes center around a very contemporary sort of anxiety that feels unique to our age,” he reflects.

Indeed, The Low Anthem’s just-budding oeuvre seems informed by a shapeless anxiety gnawing at the heart of the American experience. But it responds with beauty.

The late Phil Ochs said it well:

“Ah but in such an ugly time the true protest is beauty.”

In 2008 it netted the “Best New Act” distinction from the Boston Music Awards, and topped the “Best Album” poll in The (Providence) Phoenix.

Knox and Jeff Prystowsky started the group in 2006 after first meeting as Brown undergrads, and they’ve self-released one album a year since. Jocie Adams played clarinet on one track of the 2007 record “What The Crow Brings,” and was added as a full-fledged member in time for “…Charlie Darwin.” They’re all multi-instrumentalists, and work through various combinations of musical tools both in the studio and on stage. The new album features 27 instruments, including an “ancient” pump organ (Knox’s term), banjo, acoustic guitars, clarinet, cello, harmonica, and various forms of percussion.

“We play musical chairs in our rehearsal space and just try every different permutation of instruments, until the frequencies get excited and we know we're onto something that moves us,” Knox explains. “And when it stops moving us, then we just go back to the drawing board and try different arrangements again.”

He says they bring about a dozen different instruments out for any given show.

After spending nine months tinkering with debut “Crow” in a home studio, the band set out to record the follow-up in one “blitz” in that house on Block Island, Knox says.

“It was about ten days straight of no sleep, and it was very tense at times, but our technique for recording was to do twenty to twenty-five takes of each song, back to back, and just kind of exhaust ourselves into coming up with something.”

He says they tried 60 takes of album opener “Charlie Darwin” before they “stumbled up to” the arrangement featured on the album.

On the whole, the end effect ranges from icy, acoustic beauty (see “Charlie Darwin,” featuring falsetto vocals from Knox), to a rowdy, junkyard clamor evocative of Tom Waits. (The album’s one cover is “Home I’ll Never Be,” Tom Waits’ musical adaptation of a Jack Kerouc poem, for which Knox apparently sucked on sandpaper and assumed an entirely different vocal identity.)

In short, it’s Americana, but a timeless variety that also feels curiously placeless. With the notable exception of railroad blues “To Ohio” and the Waits/Kerouac composition, there are almost no place names on the album, nor any clear historical references. In spots, it feels like there are stretches of frostbitten prairie, an ominously inflamed horizon (stared at from a moving train), and, at the opening of the album, a terrifying expanse of cold water all around. In the mystical workingman’s-lament-cum-love-song “Ticket Taker,” the narrator sells tickets for safe passage on an “arc” and confides he “keep[s] a stock of weapons, should society collapse.”

When asked in what time and place he sees these songs unfolding, Knox pauses to consider.

“There's nothing modern about the vocabulary, and yet a lot of the scenes center around a very contemporary sort of anxiety that feels unique to our age,” he reflects.

Indeed, The Low Anthem’s just-budding oeuvre seems informed by a shapeless anxiety gnawing at the heart of the American experience. But it responds with beauty.

The late Phil Ochs said it well:

“Ah but in such an ugly time the true protest is beauty.”