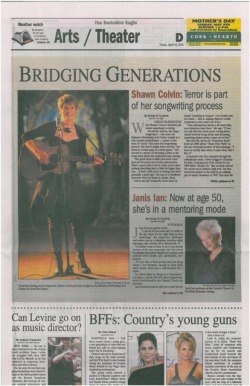

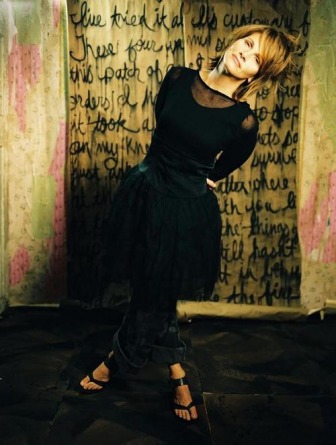

Shawn Colvin: Terror is part of her songwriting process

Published in Berkshire Eagle, 4/16/10

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

GREAT BARRINGTON—When Shawn Colvin is terrified, she knows something’s working.

For all her success, the singer-songwriter—who plays the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center tonight in a solo, acoustic performance—points to two sorts of “terror” that enter her songwriting process. The first is simply when she first “sits down to a blank page or a silent guitar.” The second is a matter of accessing a place in the brain from which true inspiration may emerge.

“The good terror is when you write a line that sort of comes out of your subconscious. That’s a great state to be in, when you're interpreting something that's a little bit bigger than you… it feels a little scary or strange and that’s generally a good sign,” she says in a telephone interview from her home in Austin.

Colvin says she frequently writes lyrics by simply “speaking in tongues” over freshly written music—that is, singing whatever words (nonsense or not) come out of her. “Your subconscious knows a lot more than your conscious mind does. If you can ride that line when you're writing lyrics, almost between being awake and dreaming, something almost always comes out of that,” she says.

She cites the chorus of “Cinnamon Road” from her 2006 album These Four Walls as but one successful product of this technique. “I have no earthly idea where it came from. But I like it!”

GREAT BARRINGTON—When Shawn Colvin is terrified, she knows something’s working.

For all her success, the singer-songwriter—who plays the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center tonight in a solo, acoustic performance—points to two sorts of “terror” that enter her songwriting process. The first is simply when she first “sits down to a blank page or a silent guitar.” The second is a matter of accessing a place in the brain from which true inspiration may emerge.

“The good terror is when you write a line that sort of comes out of your subconscious. That’s a great state to be in, when you're interpreting something that's a little bit bigger than you… it feels a little scary or strange and that’s generally a good sign,” she says in a telephone interview from her home in Austin.

Colvin says she frequently writes lyrics by simply “speaking in tongues” over freshly written music—that is, singing whatever words (nonsense or not) come out of her. “Your subconscious knows a lot more than your conscious mind does. If you can ride that line when you're writing lyrics, almost between being awake and dreaming, something almost always comes out of that,” she says.

She cites the chorus of “Cinnamon Road” from her 2006 album These Four Walls as but one successful product of this technique. “I have no earthly idea where it came from. But I like it!”

A musician who first emerged through the coffeehouse scene, Colvin snagged a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album for her 1989 debut Steady On. She certainly started her career on an industry high note, but that award was joined on the shelf by an unlikely pair of major Grammy’s in 1998. That year she netted both Song of the Year and Record of the Year for “Sunny Came Home,” a bright, catchy song that appears to be about someone deciding to commit murder.

“I snuck in and snuck back out again,” she says about her moment of mainstream ubiquity.

(She’s proven to be a darling of the Grammy’s nominating committee, accruing another seven nods, most recently for last year’s live album.)

Colvin says she doesn’t think a song like “Sunny Came Home” would sell a million records again in the current pop environment, but she’s unconcerned.

“As to where I fit in [in the business], I'm sort of past that. What I mean by that is, I have my group of fans. I’m so lucky that they still want to pay to hear me play,” Colvin says. “[Success] doesn't have to do with album sales, it's going out and touring. People still want to hear me. So that's all I need to know.”

A songwriter known for sharing a very personal perspective in her lyrics, Colvin is now writing a memoir for Harper Collins and finding the experience of writing about herself more harrowing than expected.

“I didn't know what I was getting into. Writing songs is one thing, writing prose is another thing. Without having a three or four minute time limit and a rhyme scheme, it's kind of an abyss,” she says. “It's a little strange just being conversational about it rather than poetic. When you’re being poetic, if you prefer to be a little vague you can usually manage it. But in the form of a memoir, if you're vague everybody knows you're trying to hide something.”

It’s that willingness to bare her thoughts that have helped earn Colvin the loyalty of her fans.

“Especially in a [concert] setting like I’m usually in, which is just by myself, your fans feel like familiar friends to you. They're obviously connecting with you on a level that's very close to your heart and makes you somewhat vulnerable. So in the best of worlds, I feel like there is a camaraderie between me and the fans. Things go best when I am know that they're rooting for me.”

“I snuck in and snuck back out again,” she says about her moment of mainstream ubiquity.

(She’s proven to be a darling of the Grammy’s nominating committee, accruing another seven nods, most recently for last year’s live album.)

Colvin says she doesn’t think a song like “Sunny Came Home” would sell a million records again in the current pop environment, but she’s unconcerned.

“As to where I fit in [in the business], I'm sort of past that. What I mean by that is, I have my group of fans. I’m so lucky that they still want to pay to hear me play,” Colvin says. “[Success] doesn't have to do with album sales, it's going out and touring. People still want to hear me. So that's all I need to know.”

A songwriter known for sharing a very personal perspective in her lyrics, Colvin is now writing a memoir for Harper Collins and finding the experience of writing about herself more harrowing than expected.

“I didn't know what I was getting into. Writing songs is one thing, writing prose is another thing. Without having a three or four minute time limit and a rhyme scheme, it's kind of an abyss,” she says. “It's a little strange just being conversational about it rather than poetic. When you’re being poetic, if you prefer to be a little vague you can usually manage it. But in the form of a memoir, if you're vague everybody knows you're trying to hide something.”

It’s that willingness to bare her thoughts that have helped earn Colvin the loyalty of her fans.

“Especially in a [concert] setting like I’m usually in, which is just by myself, your fans feel like familiar friends to you. They're obviously connecting with you on a level that's very close to your heart and makes you somewhat vulnerable. So in the best of worlds, I feel like there is a camaraderie between me and the fans. Things go best when I am know that they're rooting for me.”