A final act for Satchmo

Published in Berkshire Eagle, 8/24/12

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

LENOX—In the photo, a crisply dressed Louis Armstrong looks down at his trumpet, while seated in a spare, decidedly unglamorous dressing room. His well-shined shoes rest atop a shag carpet. Spare towels are stacked above a clothing rack behind him.

The image, photographed by Eddie Adams, occurred to Wall Street Journal drama critic Terry Teachout as he contemplated where to begin writing a play about the jazz legend’s life.

“A picture flashed into my mind, which is the next to last picture of Armstrong, sitting backstage in a dressing room in Las Vegas six months before he died—sitting there looking old,” Teachout recalls, emphasizing the last word. “I thought, maybe that's the moment.”

The resulting play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, makes its New England debut tonight at Shakespeare & Company’s Tina Packer Playhouse, before moving to New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre in October.

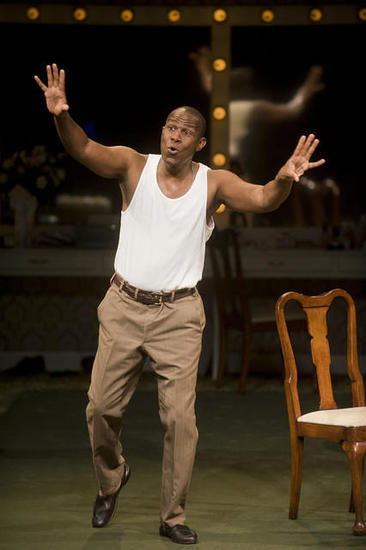

The one-man show features John Douglas Thompson, well known to Berkshire audiences for his leading roles at S&Co. in Richard III in 2010 and Othello in 2008. Teachout, who has also penned two opera librettos, wrote a 2009 biography of Armstrong that’s considered perhaps the definitive word on the musician. This is his first play. Gordon Edelstein, the artistic director at the Long Wharf whose work there and elsewhere has netted him a Lucille Lortel award and an Emmy nomination, directs.

Satchmo at the Waldorf depicts Armstrong backstage before his final show, at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel in 1971. Douglas portrays Armstrong as well as his colorful manager, Joe Glaser.

Armstrong, the grandson of slaves, was born in 1901 to a poor family in New Orleans. His father was absent, his mother worked as a prostitute, and he left school at age 11. But by the 1920’s he was recording some of the most influential sides in the New Orleans tradition, as bandleader and ace on the trumpet and cornet. From there he of course became a major crossover star, appearing in Hollywood films and on television as a smiling, friendly sort and scoring some mainstream hits.

Throughout the whole arc of his career, Teachout maintains, Armstrong remained one of the century’s great, if misunderstood, geniuses.

“By people who have only a superficial knowledge of him, he is seen as some sort of vaudeville, burlesque, Uncle Tom character,” Teachout says. “Part of his genius is that he is a genius whose work is completely accessible. The great masterpieces, the pop records like ‘Hello, Dolly,’ it's completely accessible. All you have to do is listen to it. And yet he's as important in the 20th century as Picasso is, or Proust—anybody like that. What a miracle, to be that important and yet be somebody that anybody can come to.”

Thompson says he’s spent hundreds of dollars on digital downloads of Armstrong’s music, and visited archives of his papers and personal tape recordings, to go past the amiable public persona and get to know the private man.

“I have to admit I was pretty innocent when it comes to Armstrong. I didn't know a lot about him and the little bit I knew wasn't really important to me. I disregarded him, not giving him the credit he deserves,” Thompson says, seated with Teachout and Edelstein outside the Playhouse. “But I found this play intriguing because it gave me a different history of this man.”

LENOX—In the photo, a crisply dressed Louis Armstrong looks down at his trumpet, while seated in a spare, decidedly unglamorous dressing room. His well-shined shoes rest atop a shag carpet. Spare towels are stacked above a clothing rack behind him.

The image, photographed by Eddie Adams, occurred to Wall Street Journal drama critic Terry Teachout as he contemplated where to begin writing a play about the jazz legend’s life.

“A picture flashed into my mind, which is the next to last picture of Armstrong, sitting backstage in a dressing room in Las Vegas six months before he died—sitting there looking old,” Teachout recalls, emphasizing the last word. “I thought, maybe that's the moment.”

The resulting play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, makes its New England debut tonight at Shakespeare & Company’s Tina Packer Playhouse, before moving to New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre in October.

The one-man show features John Douglas Thompson, well known to Berkshire audiences for his leading roles at S&Co. in Richard III in 2010 and Othello in 2008. Teachout, who has also penned two opera librettos, wrote a 2009 biography of Armstrong that’s considered perhaps the definitive word on the musician. This is his first play. Gordon Edelstein, the artistic director at the Long Wharf whose work there and elsewhere has netted him a Lucille Lortel award and an Emmy nomination, directs.

Satchmo at the Waldorf depicts Armstrong backstage before his final show, at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel in 1971. Douglas portrays Armstrong as well as his colorful manager, Joe Glaser.

Armstrong, the grandson of slaves, was born in 1901 to a poor family in New Orleans. His father was absent, his mother worked as a prostitute, and he left school at age 11. But by the 1920’s he was recording some of the most influential sides in the New Orleans tradition, as bandleader and ace on the trumpet and cornet. From there he of course became a major crossover star, appearing in Hollywood films and on television as a smiling, friendly sort and scoring some mainstream hits.

Throughout the whole arc of his career, Teachout maintains, Armstrong remained one of the century’s great, if misunderstood, geniuses.

“By people who have only a superficial knowledge of him, he is seen as some sort of vaudeville, burlesque, Uncle Tom character,” Teachout says. “Part of his genius is that he is a genius whose work is completely accessible. The great masterpieces, the pop records like ‘Hello, Dolly,’ it's completely accessible. All you have to do is listen to it. And yet he's as important in the 20th century as Picasso is, or Proust—anybody like that. What a miracle, to be that important and yet be somebody that anybody can come to.”

Thompson says he’s spent hundreds of dollars on digital downloads of Armstrong’s music, and visited archives of his papers and personal tape recordings, to go past the amiable public persona and get to know the private man.

“I have to admit I was pretty innocent when it comes to Armstrong. I didn't know a lot about him and the little bit I knew wasn't really important to me. I disregarded him, not giving him the credit he deserves,” Thompson says, seated with Teachout and Edelstein outside the Playhouse. “But I found this play intriguing because it gave me a different history of this man.”

Part of the allure of this play for Edelstein, who already counted himself a big Armstrong fan, was the chance to work with his music. “Music figures very heavily in my work, always has. It's probably my greatest love. I probably do love music more than I love theatre,” he says. “The piece compels me because it's about someone whose work I love, and whose work I like hearing.”

The director points to the difficulty of generating conflict with only one person onstage, and says most of the actors he’s worked with are uninterested in such roles. But Thompson is adjusting to the demands of a show with one actor but multiple characters. Glaser, who was white, Jewish, possessed mob ties and was known for his hard-nosed negotiations, presents a much different character than Armstrong. (Both did share an affinity for profanity.)

“I’m trying to get at the heart of their relationship,” Douglas says. “That's the hard part for me, but it's the part that I’m trying to go after. These two characters care about the same thing and have some of the same perspectives, but they're completely different people.”

The play was produced once before, in Orlando last year, but the rehearsal process in Lenox has featured much collaborative work among the three principals to whip it into shape. Given the star power involved, a New York run seems likely if the Long Wharf production goes well.

Teachout says he didn’t think about wading into playwriting until a theater veteran suggested it after reading his Armstrong biography. He wrote the first draft of Satchmo in four days, and the project built momentum from there.

“I didn't expect that I'd jump on the toboggan and end up at a table with John Douglas Thompson and Gordon Edelstein! That was a surprise, to put it mildly,” Teachout says. “This is actually the most exhilarating professional experience I have ever had in my entire life. Period.”

Photos by Kevin Sprague

(Full disclosure: the author of this article worked in Shakespeare & Company’s communications department for three years, ending in 2010.)

The director points to the difficulty of generating conflict with only one person onstage, and says most of the actors he’s worked with are uninterested in such roles. But Thompson is adjusting to the demands of a show with one actor but multiple characters. Glaser, who was white, Jewish, possessed mob ties and was known for his hard-nosed negotiations, presents a much different character than Armstrong. (Both did share an affinity for profanity.)

“I’m trying to get at the heart of their relationship,” Douglas says. “That's the hard part for me, but it's the part that I’m trying to go after. These two characters care about the same thing and have some of the same perspectives, but they're completely different people.”

The play was produced once before, in Orlando last year, but the rehearsal process in Lenox has featured much collaborative work among the three principals to whip it into shape. Given the star power involved, a New York run seems likely if the Long Wharf production goes well.

Teachout says he didn’t think about wading into playwriting until a theater veteran suggested it after reading his Armstrong biography. He wrote the first draft of Satchmo in four days, and the project built momentum from there.

“I didn't expect that I'd jump on the toboggan and end up at a table with John Douglas Thompson and Gordon Edelstein! That was a surprise, to put it mildly,” Teachout says. “This is actually the most exhilarating professional experience I have ever had in my entire life. Period.”

Photos by Kevin Sprague

(Full disclosure: the author of this article worked in Shakespeare & Company’s communications department for three years, ending in 2010.)