Moving beyond the past

Published in Berkshire Eagle, 2/19/10

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

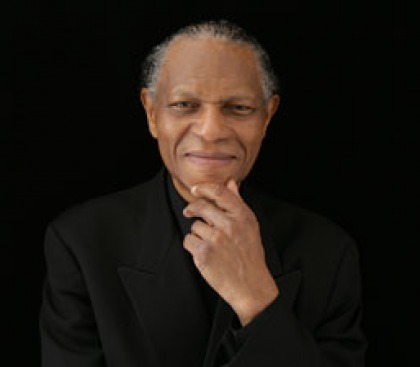

GREAT BARRINGTON—His personal career highlights include some of the finest moments in jazz history. But legendary pianist McCoy Tyner is not one to dwell on the past.

”Every once in a while I’ll go back and listen to a recording I’ve made or one I’ve been on. It’s nice to look back at what you’ve done, but I’m more interested in what I’m doing right now and what I’ll do tomorrow,” writes Tyner, who plays the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center on Sunday, in an email interview from the road. “As a musician, you can only progress if you’re moving forward.”

Moving forward is something McCoy Tyner does well.

He was just 22 when he joined John Coltrane’s band in 1960, and proceeded to make an indelible mark on some of the most influential jazz records ever made. In tandem with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones, Tyner was a bedrock of the group now known as Coltrane’s “classic quartet.” His distinctive, percussive style (often featuring clusters of single notes rather than flowing melodic figures) is heard on much-treasured albums like Giant Steps, My Favorite Things, Live! At the Village Vanguard and A Love Supreme.

Though now recognized as classic, some of this work was highly controversial in its day, with Downbeat Magazine infamously describing the torrential live album (full of expansive, modal journeys) as “anti-jazz.” In 1965, with Coltrane increasingly interested in jettisoning the vocabulary of both post-bop and modal jazz in favor of a screaming, nearly hysterical exploration of free jazz (complete with dual drummers), Tyner left the group.

Though his basic instrumental style was forged in that heady five-year period, Tyner has remained remarkably prolific over the ensuing decades, incorporating a host of musical influences and exploring a variety of band formats. He has released a long, celebrated string of recordings as bandleader, including the 1972 examination of African sounds Sahara, the bustling, busy 1980 classic Horizon, and trio record Infinity, which featured saxophonist Michael Brecker and re-launched the classic Impulse! label in 1995.

In 2008, he surprised the jazz world with Guitars, a record full of collaborations with guitarists from various musical traditions—experimentalist Marc Ribot, jazz ace John Scofield, blues-rock veteran Derek Trucks—plus always-busy banjo pioneer Béla Fleck.

GREAT BARRINGTON—His personal career highlights include some of the finest moments in jazz history. But legendary pianist McCoy Tyner is not one to dwell on the past.

”Every once in a while I’ll go back and listen to a recording I’ve made or one I’ve been on. It’s nice to look back at what you’ve done, but I’m more interested in what I’m doing right now and what I’ll do tomorrow,” writes Tyner, who plays the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center on Sunday, in an email interview from the road. “As a musician, you can only progress if you’re moving forward.”

Moving forward is something McCoy Tyner does well.

He was just 22 when he joined John Coltrane’s band in 1960, and proceeded to make an indelible mark on some of the most influential jazz records ever made. In tandem with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones, Tyner was a bedrock of the group now known as Coltrane’s “classic quartet.” His distinctive, percussive style (often featuring clusters of single notes rather than flowing melodic figures) is heard on much-treasured albums like Giant Steps, My Favorite Things, Live! At the Village Vanguard and A Love Supreme.

Though now recognized as classic, some of this work was highly controversial in its day, with Downbeat Magazine infamously describing the torrential live album (full of expansive, modal journeys) as “anti-jazz.” In 1965, with Coltrane increasingly interested in jettisoning the vocabulary of both post-bop and modal jazz in favor of a screaming, nearly hysterical exploration of free jazz (complete with dual drummers), Tyner left the group.

Though his basic instrumental style was forged in that heady five-year period, Tyner has remained remarkably prolific over the ensuing decades, incorporating a host of musical influences and exploring a variety of band formats. He has released a long, celebrated string of recordings as bandleader, including the 1972 examination of African sounds Sahara, the bustling, busy 1980 classic Horizon, and trio record Infinity, which featured saxophonist Michael Brecker and re-launched the classic Impulse! label in 1995.

In 2008, he surprised the jazz world with Guitars, a record full of collaborations with guitarists from various musical traditions—experimentalist Marc Ribot, jazz ace John Scofield, blues-rock veteran Derek Trucks—plus always-busy banjo pioneer Béla Fleck.

“Sometimes, the best way to change the sound or direction of a familiar tune is to add an unfamiliar voice to the mix,” Tyner writes. “Over the last few years I’ve had Marc Ribot as a special guest in my band, and he always takes the music in a different direction because he hears things differently than a lot of other guitarists.”

Though he’s not one to romanticize his own accomplishments or dally in nostalgia, Tyner is happy to re-visit compositions he’s previously recorded in iconic versions, in order to explore them in fresh ways with new generations of artists.

“There’s always something new that can be learned no matter how many times you’ve played a song. Guys like John Scofield and Béla Fleck are so creative that even just one improvised note or phrase can take the music in a different direction. That new direction might change subsequent solos, and might change the way you play the head out,” Tyner writes of the composed portion of a song that frames the improvised solos. “All of a sudden you’ve got something new and fresh, and you learn from that.”

He also names drummer Francisco Mela and trumpeter Christian Scott as among the more exciting younger musicians he’s played with in recent years. Of this influence from a new generation, Tyner writes: “It keeps me going!”

Tyner is touring as part of a trio these days, joined onstage by bassist Gerald Cannon and drummer Eric Kamau Gravatt. “Eric and Gerald have been playing with me for some time now. The more we play together, the more comfortable they get with my music, which allows them to open things up and bring in fresh ideas and sounds.”

Though Tyner’s impeccable resume draws jazz fans eager to see the master at work, he insists that his band is not simply a showcase for his own piano chops.

“As a pianist and a bandleader, I think it’s just as important to accompany band members as it is to take a solo. You can tell when a trio is really listening to each other—it’s about the group sound, not the individual soloist.”

Perhaps. But whenever Tyner moves forward, others are likely to follow.

Comment on this article

Though he’s not one to romanticize his own accomplishments or dally in nostalgia, Tyner is happy to re-visit compositions he’s previously recorded in iconic versions, in order to explore them in fresh ways with new generations of artists.

“There’s always something new that can be learned no matter how many times you’ve played a song. Guys like John Scofield and Béla Fleck are so creative that even just one improvised note or phrase can take the music in a different direction. That new direction might change subsequent solos, and might change the way you play the head out,” Tyner writes of the composed portion of a song that frames the improvised solos. “All of a sudden you’ve got something new and fresh, and you learn from that.”

He also names drummer Francisco Mela and trumpeter Christian Scott as among the more exciting younger musicians he’s played with in recent years. Of this influence from a new generation, Tyner writes: “It keeps me going!”

Tyner is touring as part of a trio these days, joined onstage by bassist Gerald Cannon and drummer Eric Kamau Gravatt. “Eric and Gerald have been playing with me for some time now. The more we play together, the more comfortable they get with my music, which allows them to open things up and bring in fresh ideas and sounds.”

Though Tyner’s impeccable resume draws jazz fans eager to see the master at work, he insists that his band is not simply a showcase for his own piano chops.

“As a pianist and a bandleader, I think it’s just as important to accompany band members as it is to take a solo. You can tell when a trio is really listening to each other—it’s about the group sound, not the individual soloist.”

Perhaps. But whenever Tyner moves forward, others are likely to follow.

Comment on this article