Always moving forward, always Herbie

Published in Berkshire Eagle, 8/6/10

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

Who is Herbie Hancock?

The shape-shifting, 70-year old maestro is that rare breed of musical legend who's managed to stay stubbornly relevant across the decades, an emblematic figure in a handful of divergent styles—with adherents of each niche viewing their preferred version as "the" Herbie.

His latest incarnation is as a globe-trotting, world music impresario. His latest release is The Imagine Project, a conceptual, cross-genre affair recorded over two years in studios around the world. The high-minded, defiantly earnest project is explained as an attempt to inspire peaceful global collaboration through its own example. Hancock will highlight material from this feel-good musical summit in a much-anticipated show at Tanglewood on Monday.

When asked if he feels his sound must always be moving forward, he responds in the affirmative.

"The alternative is for it to stand still. If it's actually standing still, it's moving backwards. Because the clock is continually ticking—it doesn't stop," Hancock says, during a telephone interview from Spain during a July tour. "So you're never really still. It's part of my nature to look for new ways of doing things. I've always done that. My whole history's about that."

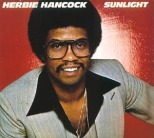

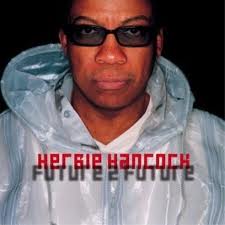

It’s a history with many chapters. There's that of the post-bop pioneer, who created acoustic jazz of a sort that's been matched by some of the other greats but not surpassed. There’s the Herbie of the indefatigable Head Hunters, an album discovered and re-discovered by generations of younger listeners as a mind-blowing document of electro-funk. Hancock's 1983 Future Shock album, and particularly its unlikely hit single "Rockit," remains an indelible artifact of the first-generation MTV era. His 2001 album Future 2 Future managed to incorporate the textures of electronic music—particularly drum and bass—in a manner that sidestepped some of the more ham-handed crossover attempts then current.

And in recent years he's ascended to an eminently accessible, elder statesman status that transcends genre. He’s stocked his albums with all-star guest spots, and authored the second jazz album ever to win the Grammy for Album of the Year—for a re-imagining of the work of Joni Mitchell, no less.

Though his progress has been anything but linear, Hancock says he can see the thread that runs through all this work.

Who is Herbie Hancock?

The shape-shifting, 70-year old maestro is that rare breed of musical legend who's managed to stay stubbornly relevant across the decades, an emblematic figure in a handful of divergent styles—with adherents of each niche viewing their preferred version as "the" Herbie.

His latest incarnation is as a globe-trotting, world music impresario. His latest release is The Imagine Project, a conceptual, cross-genre affair recorded over two years in studios around the world. The high-minded, defiantly earnest project is explained as an attempt to inspire peaceful global collaboration through its own example. Hancock will highlight material from this feel-good musical summit in a much-anticipated show at Tanglewood on Monday.

When asked if he feels his sound must always be moving forward, he responds in the affirmative.

"The alternative is for it to stand still. If it's actually standing still, it's moving backwards. Because the clock is continually ticking—it doesn't stop," Hancock says, during a telephone interview from Spain during a July tour. "So you're never really still. It's part of my nature to look for new ways of doing things. I've always done that. My whole history's about that."

It’s a history with many chapters. There's that of the post-bop pioneer, who created acoustic jazz of a sort that's been matched by some of the other greats but not surpassed. There’s the Herbie of the indefatigable Head Hunters, an album discovered and re-discovered by generations of younger listeners as a mind-blowing document of electro-funk. Hancock's 1983 Future Shock album, and particularly its unlikely hit single "Rockit," remains an indelible artifact of the first-generation MTV era. His 2001 album Future 2 Future managed to incorporate the textures of electronic music—particularly drum and bass—in a manner that sidestepped some of the more ham-handed crossover attempts then current.

And in recent years he's ascended to an eminently accessible, elder statesman status that transcends genre. He’s stocked his albums with all-star guest spots, and authored the second jazz album ever to win the Grammy for Album of the Year—for a re-imagining of the work of Joni Mitchell, no less.

Though his progress has been anything but linear, Hancock says he can see the thread that runs through all this work.

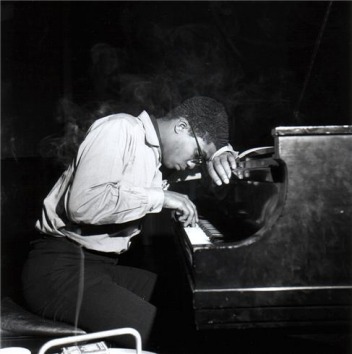

I couldn't track down the credit for this classic photo...anyone?

“I see that I have been a perennial student. And that really is kind of the bottom line. Along with that is the curiosity that's a part of my being—and I'm an optimist, and that's very much a part of my being too.”

These reflections on his work are wrung from Hancock with some effort; he has bigger things on his mind. Before discussing the musical specifics of the new project and how it flows from his previous work, he first speaks at some length about the political scene in America, painting in broad rhetorical strokes about “the people” and “the politicians” and “globalization.”

The worldwide impact of America’s financial crisis brought home the interconnectedness of the globe, he says—but portrayed only the negative consequences of this reality. These concerns gave birth to The Imagine Project. In fact, he wasn’t sure he even wanted to make another album unless he could find a way to tie it to social issues of great consequence.

Why put the concept at the forefront? Couldn’t the world simply use another great Herbie Hancock record?

“The world has a whole bunch of Herbie Hancock records,” he responds. “I think that answers your question. The world doesn't have a lot of The Imagine Project. There's only one.”

He ticks off the stats: the album features seven languages and was recorded in seven different countries, with artists representing 11 nations. Most of the material is uplifting and familiar, including John Lennon’s titular anthem, Peter Gabriel’s “Don’t Give Up,” Mathew Moore’s “Space Captain” (with its refrain about “learning to live together,”) and Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changing.”

“There's a lot of hope on this record,” he explains. “People are desperate—especially Americans—and they need hope.”

These reflections on his work are wrung from Hancock with some effort; he has bigger things on his mind. Before discussing the musical specifics of the new project and how it flows from his previous work, he first speaks at some length about the political scene in America, painting in broad rhetorical strokes about “the people” and “the politicians” and “globalization.”

The worldwide impact of America’s financial crisis brought home the interconnectedness of the globe, he says—but portrayed only the negative consequences of this reality. These concerns gave birth to The Imagine Project. In fact, he wasn’t sure he even wanted to make another album unless he could find a way to tie it to social issues of great consequence.

Why put the concept at the forefront? Couldn’t the world simply use another great Herbie Hancock record?

“The world has a whole bunch of Herbie Hancock records,” he responds. “I think that answers your question. The world doesn't have a lot of The Imagine Project. There's only one.”

He ticks off the stats: the album features seven languages and was recorded in seven different countries, with artists representing 11 nations. Most of the material is uplifting and familiar, including John Lennon’s titular anthem, Peter Gabriel’s “Don’t Give Up,” Mathew Moore’s “Space Captain” (with its refrain about “learning to live together,”) and Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changing.”

“There's a lot of hope on this record,” he explains. “People are desperate—especially Americans—and they need hope.”

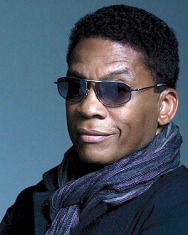

Deal with this

Photo: Klaus Muempfer

Among the guests are popsters Pink and Seal, bluesy husband-and-wife duo Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks, Congolese group Konono No. 1 and Columbian guitarist Juanes. On the Dylan song, the Irish folk sounds of The Chieftans intermingle with the airy improvisations of Malinese kora master Toumani Diabaté; for new composition “The Song Goes On,” the tenor sax of old Miles alum Wayne Shorter darts around the sitar work of Anoushka Shankar and the vocals of Chaka Khan. (Onstage, the musical duties are re-distributed among a six-piece band.) Hancock traveled to his collaborators’ home countries whenever possible for the recording, and though the overall feeling is of a carefully put-together pop album produced with the expectation of accolades, many of the songs preserve a feel that is loose, and—for lack of a better word—jazzy.

“We wanted that improvisational, in-the-moment spirit. That's the spirit of change. That's the spirit of the seeking mind,” Hancock enthuses. “That’s what The Imagine Project is all about. We need to develop a new spirit of activism toward creating the kind of globalization that we want. The purpose of me personally doing this record is because I want to show by my example as a cultural artist that human beings have infinite capacity to create new ways of looking at things.”

There’s no guarantee the album will prove the clarion call to a new vision of globalization. But it’s indeed stocked with new ways of looking at and listening to things—and, if nothing else, one might say that’s been Herbie Hancock’s specialty.

“We wanted that improvisational, in-the-moment spirit. That's the spirit of change. That's the spirit of the seeking mind,” Hancock enthuses. “That’s what The Imagine Project is all about. We need to develop a new spirit of activism toward creating the kind of globalization that we want. The purpose of me personally doing this record is because I want to show by my example as a cultural artist that human beings have infinite capacity to create new ways of looking at things.”

There’s no guarantee the album will prove the clarion call to a new vision of globalization. But it’s indeed stocked with new ways of looking at and listening to things—and, if nothing else, one might say that’s been Herbie Hancock’s specialty.