Rollins keeps on showing up

Published in Berkshire Eagle, 3/23/11

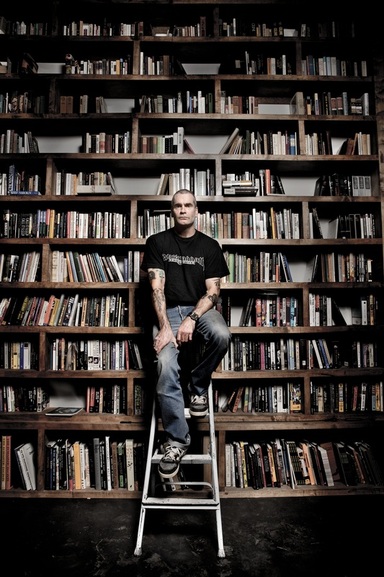

Photo by Chapman Baehler

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

NORFOLK, Conn.—Henry Rollins likes to stay busy.

The spoken word performer, writer, actor, radio host, voiceover talent, erstwhile musician and all-around Renaissance man brings his latest talking tour to Infinity Hall this evening, in a performance that's likely to include anecdotes culled from Rollins' world travels as well as barbed commentary on current events.

Tonight's performance comes shortly after his 50th birthday and amid a run of 24 shows in 27 days, following up on a prior series of gigs last month. Pointing to the 11 months of touring he envisions for 2012, Rollins insists this present jaunt is nothing.

"It's constant, but it's kind of how I do it," he says in a telephone interview from Annapolis, Maryland, where he's due onstage in several hours. “It's not like I have to hurl spears at the sun, I'm just onstage every night talking. It's a grind I like, and it’s a grind I'm very familiar with.”

Rollins first came to prominence as the vocalist for seminal 1980's punk outfit Black Flag, and went on to become one of the most recognizable personalities in the world of 1990's alternative rock—for the genre-bending hard rock of his Rollins Band as well as acerbic guest hosting duties on MTV and frequent film appearances, including Al Pacino/Robert Deniro crime thriller Heat and David Lynch's Lost Highway.

Though high profile concert performances in the first Lollapalooza festival in 1991 and Woodstock '94 provided his mainstream breakthrough, it's Henry Rollins, the personality, that has earned the most pop cultural salience. Whether dissecting films on IFC, writing regular columns in Vanity Fair and LA Weekly, hosting a weekly radio program on Los Angeles' influential KCRW, or starting a publishing company to release his series of journal-style books full of brutally honest personal details mixed with cultural observations, it's the man's fiery personality and catholic interests that fuel his many high-profile—and simultaneous—careers. In fact, it’s the spoken word recording of his well regarded Black Flag-era tour journal Get in the Van that won him his sole Grammy.

NORFOLK, Conn.—Henry Rollins likes to stay busy.

The spoken word performer, writer, actor, radio host, voiceover talent, erstwhile musician and all-around Renaissance man brings his latest talking tour to Infinity Hall this evening, in a performance that's likely to include anecdotes culled from Rollins' world travels as well as barbed commentary on current events.

Tonight's performance comes shortly after his 50th birthday and amid a run of 24 shows in 27 days, following up on a prior series of gigs last month. Pointing to the 11 months of touring he envisions for 2012, Rollins insists this present jaunt is nothing.

"It's constant, but it's kind of how I do it," he says in a telephone interview from Annapolis, Maryland, where he's due onstage in several hours. “It's not like I have to hurl spears at the sun, I'm just onstage every night talking. It's a grind I like, and it’s a grind I'm very familiar with.”

Rollins first came to prominence as the vocalist for seminal 1980's punk outfit Black Flag, and went on to become one of the most recognizable personalities in the world of 1990's alternative rock—for the genre-bending hard rock of his Rollins Band as well as acerbic guest hosting duties on MTV and frequent film appearances, including Al Pacino/Robert Deniro crime thriller Heat and David Lynch's Lost Highway.

Though high profile concert performances in the first Lollapalooza festival in 1991 and Woodstock '94 provided his mainstream breakthrough, it's Henry Rollins, the personality, that has earned the most pop cultural salience. Whether dissecting films on IFC, writing regular columns in Vanity Fair and LA Weekly, hosting a weekly radio program on Los Angeles' influential KCRW, or starting a publishing company to release his series of journal-style books full of brutally honest personal details mixed with cultural observations, it's the man's fiery personality and catholic interests that fuel his many high-profile—and simultaneous—careers. In fact, it’s the spoken word recording of his well regarded Black Flag-era tour journal Get in the Van that won him his sole Grammy.

Photo by Chapman Baehler

Is there

something compulsive in his need to go in so many different directions?

“Probably, yeah,” he says, “and probably a bit of desperation and a bit of fear of sitting still. And a fear of dealing with things, like real life. That's one of the reasons I tour so much. Real life is kind of a drag to me. By the second Saturday I've been off the road, I start to feel really anxious because of the degree of comfort I feel when I'm off the road. The house I live in is a nice place to live—it's so nice it'll kill ya.”

Rollins has a nagging fear of complacency, as if every moment he spends, say, relaxing with a biography of painter Francis Bacon is aiding the bad guys of the world in their ongoing getaway. The presence at home of all his favorite records and books, and the opportunity to enjoy them, is a problem. “That’s something you should be doing when you’re 80. To me, enjoyment is taking your eye off the ball. I feel a duty to stay out in the world.”

He has a blue collar work ethic dating back to his days scooping ice cream in a Washington, DC Hägen-Dazstore—the unassuming perch from which he auditioned to join Black Flag as a 20-year old with “a high school education and no real aspirations,” he recalls.

“For me over the years, I just keep showing up for work. I've taken my minimum wage working mentality and I've gone forth with it. I'm not an artist, I have really no artistic meaning. To me, I'm just processing information. I don't take myself seriously but I take the audience with an overwhelming degree of seriousness. I’m kind of obsessed with that.”

“Probably, yeah,” he says, “and probably a bit of desperation and a bit of fear of sitting still. And a fear of dealing with things, like real life. That's one of the reasons I tour so much. Real life is kind of a drag to me. By the second Saturday I've been off the road, I start to feel really anxious because of the degree of comfort I feel when I'm off the road. The house I live in is a nice place to live—it's so nice it'll kill ya.”

Rollins has a nagging fear of complacency, as if every moment he spends, say, relaxing with a biography of painter Francis Bacon is aiding the bad guys of the world in their ongoing getaway. The presence at home of all his favorite records and books, and the opportunity to enjoy them, is a problem. “That’s something you should be doing when you’re 80. To me, enjoyment is taking your eye off the ball. I feel a duty to stay out in the world.”

He has a blue collar work ethic dating back to his days scooping ice cream in a Washington, DC Hägen-Dazstore—the unassuming perch from which he auditioned to join Black Flag as a 20-year old with “a high school education and no real aspirations,” he recalls.

“For me over the years, I just keep showing up for work. I've taken my minimum wage working mentality and I've gone forth with it. I'm not an artist, I have really no artistic meaning. To me, I'm just processing information. I don't take myself seriously but I take the audience with an overwhelming degree of seriousness. I’m kind of obsessed with that.”