Published in Preview Massachusetts (March 2009)

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

Béla Fleck is used to speaking many musical languages. But it’s usually with partners who at least share a spoken one.

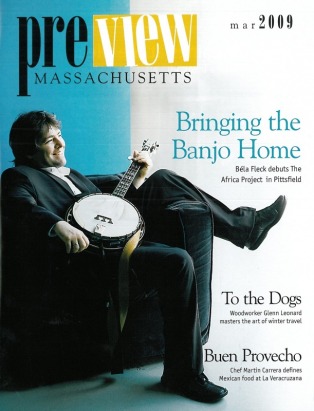

Now this much-decorated banjo virtuoso is about to embark on a tour with a group of African musicians who’ve never played together, debuting a repertoire he’s never performed for an audience. For the guy who’s played with everybody, this is a new one.

"It's tough going. It's a lot of factors that I'm not used to dealing with to make it all come off. So I'm a little nervous about it, frankly," the eight-time Grammy winner says in a telephone interview from his home in Nashville.

His calm and easy voice, touched with a tiny bit of Southern twang. quickens a bit as he ticks off some of the challenges. “Is everybody going to show up? Am I going to be able to get everybody onstage? I won't be able to speak their language. I know it's going to be amazing, but it's definitely a hard job."

In a big coup for we locals, this grand experiment—Béla Fleck’s The Africa Project—kicks off with a world debut performance at Pittsfield’s Colonial Theatre on March 26. When they all get together to rehearse in Western Massachusetts before the Pittsfield show, it will be the first time these cats all stand together in the same room, playing music.

The tour features a hand picked ensemble of musicians who are masters in their own spheres, but don’t exactly have lots of experience jamming with banjo players. While the idea of mixing the banjo with African folk music may sound at first like an academic experiment, it in fact unites two seemingly disparate musical traditions that came from the same place.

It’s bringing the banjo home.

Béla Fleck is used to speaking many musical languages. But it’s usually with partners who at least share a spoken one.

Now this much-decorated banjo virtuoso is about to embark on a tour with a group of African musicians who’ve never played together, debuting a repertoire he’s never performed for an audience. For the guy who’s played with everybody, this is a new one.

"It's tough going. It's a lot of factors that I'm not used to dealing with to make it all come off. So I'm a little nervous about it, frankly," the eight-time Grammy winner says in a telephone interview from his home in Nashville.

His calm and easy voice, touched with a tiny bit of Southern twang. quickens a bit as he ticks off some of the challenges. “Is everybody going to show up? Am I going to be able to get everybody onstage? I won't be able to speak their language. I know it's going to be amazing, but it's definitely a hard job."

In a big coup for we locals, this grand experiment—Béla Fleck’s The Africa Project—kicks off with a world debut performance at Pittsfield’s Colonial Theatre on March 26. When they all get together to rehearse in Western Massachusetts before the Pittsfield show, it will be the first time these cats all stand together in the same room, playing music.

The tour features a hand picked ensemble of musicians who are masters in their own spheres, but don’t exactly have lots of experience jamming with banjo players. While the idea of mixing the banjo with African folk music may sound at first like an academic experiment, it in fact unites two seemingly disparate musical traditions that came from the same place.

It’s bringing the banjo home.

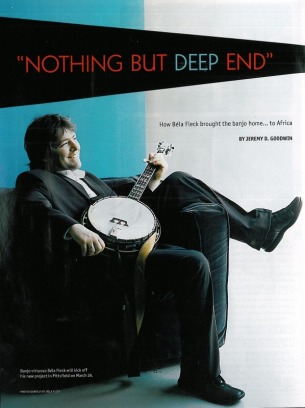

Fleck’s ever-evolving body of work, including collaborations with everyone from jazz great Chick Corea to French violin innovator Jean-Luc Ponty, has made him undisputed master of Appalachia fusion. His Grammy stats say it all: he’s won in jazz, pop, country and classical categories, and also been nominated in spoken word, bluegrass, and world music ones. His dense resume reveals a compulsively creative artist, one committed to bringing the banjo to exciting and sometimes disorienting new places. And yet he’s described his latest endeavor as “the most ambitious project I have taken on.”

The Africa Project is a multi-pronged affair spun from Fleck’s musical odyssey across African in 2005. His brother Sascha Paladino directed a film documenting the trip, “Throw Down Your Heart,” and an album of the same name is culled almost totally from uncut recordings made while Fleck trekked through Uganda, Tanzania, The Gambia and Mali. (The DVD and the album were expected in late February or early March, with a limited theatrical release of the film possible.)

The shape of the shows is very much in flux. Fleck envisions each artist—guitarist D’Gary from Madagascar, with his percussionist Mario; guitarist Vusi Mahlesela from South Africa; kora master Toumani Diabate from Mali; and Tanzanian thumb piano virtuoso Anania Ngoglia, with guitar accompanist John Kitme—playing solo sets of their own songs, joining with Fleck for some numbers, and then assembling into a group ensemble for the finale.

This initial run of 15 dates will be followed by another tour in June and July with different musicians in a bigger, louder band. But these first shows will be intimate, acoustic, intense.

“One of the things I really liked about the film in general is a lot of these very intimate interactions between me and these different musicians. [The shows on this tour are] not going to be this big rockin’ sockin’ Afropop thing,” Fleck says. “This stuff is going to cook, [but] it's going to cook delicately.”

The Africa Project is a multi-pronged affair spun from Fleck’s musical odyssey across African in 2005. His brother Sascha Paladino directed a film documenting the trip, “Throw Down Your Heart,” and an album of the same name is culled almost totally from uncut recordings made while Fleck trekked through Uganda, Tanzania, The Gambia and Mali. (The DVD and the album were expected in late February or early March, with a limited theatrical release of the film possible.)

The shape of the shows is very much in flux. Fleck envisions each artist—guitarist D’Gary from Madagascar, with his percussionist Mario; guitarist Vusi Mahlesela from South Africa; kora master Toumani Diabate from Mali; and Tanzanian thumb piano virtuoso Anania Ngoglia, with guitar accompanist John Kitme—playing solo sets of their own songs, joining with Fleck for some numbers, and then assembling into a group ensemble for the finale.

This initial run of 15 dates will be followed by another tour in June and July with different musicians in a bigger, louder band. But these first shows will be intimate, acoustic, intense.

“One of the things I really liked about the film in general is a lot of these very intimate interactions between me and these different musicians. [The shows on this tour are] not going to be this big rockin’ sockin’ Afropop thing,” Fleck says. “This stuff is going to cook, [but] it's going to cook delicately.”

Sometimes home is where the akonting is.

That’s how it is for the banjo, the unofficial emblem of white Appalachia.

It’s seen by many today as the most American of instruments, but an earlier version of the banjo came across the Atlantic with African slaves, and is likely descended from this three-stringed instrument, still played in western Africa.

In fact, when pioneering musicologist Alan Lomax looked to re-create the sound of colonial-era Williamsburg for a film in 1960, he assembled a group including the black Sea Island Singers of Georgia (with their repertoire of slave-era work songs, shouts and sea chanteys) and white banjo ace Hobart Smith, maestro of the Virginia mountains.

"Some part of me has always been bothered about the idea that so many people think it's a white, southern instrument, and that's all there is to the banjo's history. I would say that bluegrass is [only] the latest resurgence of the banjo," Fleck says.

It’s a striking statement. This rich history aside, the fact remains the banjo today is the great voice of bluegrass, a very American—and, yes, very white—genre of music. So to find a place for the banjo in African folk music, and tour the United States with the results, inevitably makes a cultural statement along with the musical one.

Mickey Hart, founding drummer for the Grateful Dead, won the first-ever Grammy for Best World Music Album in 1991 when he brought together drummers and percussionists from Brazil, West Africa, India, and the United States for “Planet Drum.” His work as a musicologist earned him a “Living Legend” award from the Library of Congress.

“The kind of stuff that Béla is doing, it couldn't be better. It’s bringing cultures together,” Hart says in a telephone interview. “It's like a handshake. As an American playing an instrument of African origin, it's a wonderful handshake culturally, musicologicly. The social anthropology behind this is just extraordinary.”

This aspect of the project is potent but left understated.

"I'm not a musicologist. I just love great music and I love the banjo and I wanted to go find great musicians in Africa to play with," Fleck says with obvious, earnest enthusiasm. "It's musical. I wanna play great music with people. That's what I'm into."

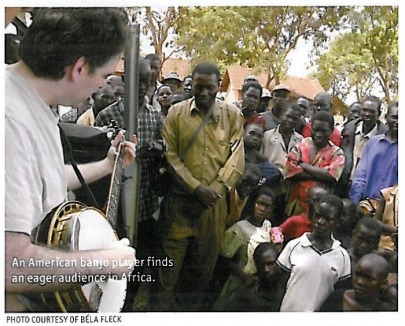

Yet, in the film, when he makes it to The Gambia and stands in an open air courtyard playing alongside two akonting players in the band The Jatta Family, it’s hard not to feel there’s something else going on—something, well, important—besides the music.

***

This is not an isolated example; “Throw Down Your Heart” offers a feast of memorable musical moments.

A particularly transporting jam between Fleck on banjo and blind maestro Anania on thumb piano occurs on the steps of a deserted-looking building in Tanzania, while a few children bicycle by, seemingly unaware. (The thumb piano is a wooden board with thin metal keys attached, which vibrate when plucked. It makes a sound not unlike a vibraphone.)

This is one of many chill-inducing moments caught on film and the similarly stellar companion record. Another scene captures Fleck playing with a Ugandan community band built around a thunderous, 12-foot folk marimba, complete with dancing toddlers and jubilant, hand-clapping elders.

While he logged studio time with professional musicians later in the trip, Fleck had no one specifically lined up at his first stop, Uganda. He had to find and audition musicians, learn their songs, and then record, all in the span of several days. Did he dive into the deep end right at the beginning?

“There was nothing but deep end, honestly,” he confides. “Every single thing we did was so out of my comfort zone that we had to just really go in there with a very positive attitude and just enjoy the craziness of what was coming.”

And so we get The Africa Project—including a film, an album, a tour, and another tour to come. Altogether, it includes dance music, meditative jams, rootsy folk sounds and flashy instrumental fireworks. There’s broken English and flowing musical conversations. At the center is an instrument that seems so out of place, but is really back at home. And maybe there’s even something in there about people—whether more used to hearing, for instance, the banjo or the akonting—and what they really have to say to each other.

—————————————————--

That’s how it is for the banjo, the unofficial emblem of white Appalachia.

It’s seen by many today as the most American of instruments, but an earlier version of the banjo came across the Atlantic with African slaves, and is likely descended from this three-stringed instrument, still played in western Africa.

In fact, when pioneering musicologist Alan Lomax looked to re-create the sound of colonial-era Williamsburg for a film in 1960, he assembled a group including the black Sea Island Singers of Georgia (with their repertoire of slave-era work songs, shouts and sea chanteys) and white banjo ace Hobart Smith, maestro of the Virginia mountains.

"Some part of me has always been bothered about the idea that so many people think it's a white, southern instrument, and that's all there is to the banjo's history. I would say that bluegrass is [only] the latest resurgence of the banjo," Fleck says.

It’s a striking statement. This rich history aside, the fact remains the banjo today is the great voice of bluegrass, a very American—and, yes, very white—genre of music. So to find a place for the banjo in African folk music, and tour the United States with the results, inevitably makes a cultural statement along with the musical one.

Mickey Hart, founding drummer for the Grateful Dead, won the first-ever Grammy for Best World Music Album in 1991 when he brought together drummers and percussionists from Brazil, West Africa, India, and the United States for “Planet Drum.” His work as a musicologist earned him a “Living Legend” award from the Library of Congress.

“The kind of stuff that Béla is doing, it couldn't be better. It’s bringing cultures together,” Hart says in a telephone interview. “It's like a handshake. As an American playing an instrument of African origin, it's a wonderful handshake culturally, musicologicly. The social anthropology behind this is just extraordinary.”

This aspect of the project is potent but left understated.

"I'm not a musicologist. I just love great music and I love the banjo and I wanted to go find great musicians in Africa to play with," Fleck says with obvious, earnest enthusiasm. "It's musical. I wanna play great music with people. That's what I'm into."

Yet, in the film, when he makes it to The Gambia and stands in an open air courtyard playing alongside two akonting players in the band The Jatta Family, it’s hard not to feel there’s something else going on—something, well, important—besides the music.

***

This is not an isolated example; “Throw Down Your Heart” offers a feast of memorable musical moments.

A particularly transporting jam between Fleck on banjo and blind maestro Anania on thumb piano occurs on the steps of a deserted-looking building in Tanzania, while a few children bicycle by, seemingly unaware. (The thumb piano is a wooden board with thin metal keys attached, which vibrate when plucked. It makes a sound not unlike a vibraphone.)

This is one of many chill-inducing moments caught on film and the similarly stellar companion record. Another scene captures Fleck playing with a Ugandan community band built around a thunderous, 12-foot folk marimba, complete with dancing toddlers and jubilant, hand-clapping elders.

While he logged studio time with professional musicians later in the trip, Fleck had no one specifically lined up at his first stop, Uganda. He had to find and audition musicians, learn their songs, and then record, all in the span of several days. Did he dive into the deep end right at the beginning?

“There was nothing but deep end, honestly,” he confides. “Every single thing we did was so out of my comfort zone that we had to just really go in there with a very positive attitude and just enjoy the craziness of what was coming.”

And so we get The Africa Project—including a film, an album, a tour, and another tour to come. Altogether, it includes dance music, meditative jams, rootsy folk sounds and flashy instrumental fireworks. There’s broken English and flowing musical conversations. At the center is an instrument that seems so out of place, but is really back at home. And maybe there’s even something in there about people—whether more used to hearing, for instance, the banjo or the akonting—and what they really have to say to each other.

—————————————————--