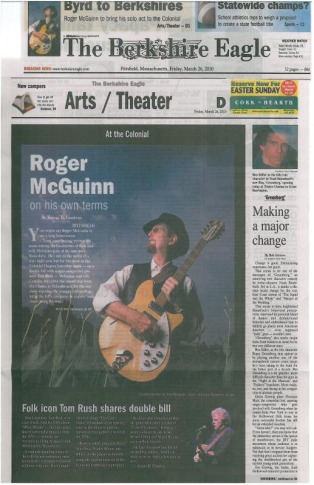

Roger McGuinn: On his own terms

Published in the Berkshire Eagle, 3/26/10

Photo: John Chiasson

By Jeremy D. Goodwin

PITTSFIELD—You might say Roger McGuinn is on a long honeymoon.

Long since having written his name among the luminaries of rock and roll, McGuinn goes at his own pace these days. He's not in the midst of a tour right now, but for his show at the Colonial Theatre tomorrow night—on a double bill with singer-songwriter pioneer Tom Rush—McGuinn and wife Camilla will drive the round trip from their home in Orlando just for the one show, enjoying the scenery and perhaps using the GPS navigator to explore back roads along the way.

Forty years after the peak of his commercial success with The Byrds, McGuinn has earned the right to do things on his own terms. He tours as a solo act, with Camilla—by turns his business manager, songwriting partner, and roadie—alongside, engaging in a long series of epic road trips.

"We travel by road and by oceanliner and train. I stay off the planes because they're rough on instruments," McGuinn explains in a morning telephone interview from his home. "It's just a lot of fun. You turn back the clock a hundred years and enjoy the slow progress of getting somewhere."

His signature work with The Byrds was concentrated into just a handful of years, but has proven to be hugely influential. (The Byrds were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991.) The specific sound McGuinn achieved with a 12-string Rickenbacker guitar run through a tube compressor, combined with a banjo-influenced fingerpicking style inherited from his folk days, amounts nearly to a genre unto itself.

Amazingly, the band is credited by some with spawning two key genres—folk rock and country rock. Though they were hardly working in a vacuum (Bob Dylan's role in the birth of each movement can hardly be overstated, for instance), the work of McGuinn and company has been filtered down, in part, through bands from The Velvet Underground to R.E.M.

"There's not much to say about that. Just like people are influenced by Chuck Berry or The Beatles or the Everly Brothers, it's just one of the things out there," he says of his old band’s influence. "The jingle-jangle Rickenbacker sound is something people picked up on, but a lot of people don't know where it came from. They just hear it as one of the textures of music that are out there."

PITTSFIELD—You might say Roger McGuinn is on a long honeymoon.

Long since having written his name among the luminaries of rock and roll, McGuinn goes at his own pace these days. He's not in the midst of a tour right now, but for his show at the Colonial Theatre tomorrow night—on a double bill with singer-songwriter pioneer Tom Rush—McGuinn and wife Camilla will drive the round trip from their home in Orlando just for the one show, enjoying the scenery and perhaps using the GPS navigator to explore back roads along the way.

Forty years after the peak of his commercial success with The Byrds, McGuinn has earned the right to do things on his own terms. He tours as a solo act, with Camilla—by turns his business manager, songwriting partner, and roadie—alongside, engaging in a long series of epic road trips.

"We travel by road and by oceanliner and train. I stay off the planes because they're rough on instruments," McGuinn explains in a morning telephone interview from his home. "It's just a lot of fun. You turn back the clock a hundred years and enjoy the slow progress of getting somewhere."

His signature work with The Byrds was concentrated into just a handful of years, but has proven to be hugely influential. (The Byrds were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991.) The specific sound McGuinn achieved with a 12-string Rickenbacker guitar run through a tube compressor, combined with a banjo-influenced fingerpicking style inherited from his folk days, amounts nearly to a genre unto itself.

Amazingly, the band is credited by some with spawning two key genres—folk rock and country rock. Though they were hardly working in a vacuum (Bob Dylan's role in the birth of each movement can hardly be overstated, for instance), the work of McGuinn and company has been filtered down, in part, through bands from The Velvet Underground to R.E.M.

"There's not much to say about that. Just like people are influenced by Chuck Berry or The Beatles or the Everly Brothers, it's just one of the things out there," he says of his old band’s influence. "The jingle-jangle Rickenbacker sound is something people picked up on, but a lot of people don't know where it came from. They just hear it as one of the textures of music that are out there."

From one of McGuinn's three instructional videos

Has anybody seen my guitar?

After the dissolution of The Byrds in the early '70s, and a series of full or partial reunions, McGuinn pretty much sat out the 1980's as a recording artist, instead pursuing "Jack Kerouac-inspired adventures," as described on his Web site. (“The whole idea of the freedom of the open road and just barnstorming around—there's nothing like it,” he says.) From time to time he's emerged to make a splash, whether testifying before a Senate committee in 2000 about digital music distribution (he's a booster) or releasing a well-received solo effort like Back From Rio in 1991.

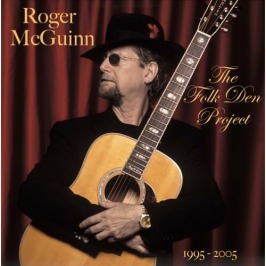

McGuinn has created a huge body of work since 1995 with his Folk Den Project, recording an acoustic version of a traditional folk song once a month and making it available for free online along with chords and background info on the songs and his connection to them. (The project has been spun off into three for-sale collections--one was nominated for a Grammy and another is an exhaustive four-CD compendium.) His latest studio album, Limited Edition (released in 2004) features several folk and blues songs electrified by his signature "jingle-jangle" style, plus seven new songs co-written with Camilla.

"I started it out of a genuine concern that the traditional side of folk was being neglected. Most people are singer-songwriters, because there' s more money in it," he says. "A lot of people don't even know it exists. They're brought up in a culture with other music and they've never even heard of it. So I'm just doing my part to keep it alive."

(continued below...)

McGuinn has created a huge body of work since 1995 with his Folk Den Project, recording an acoustic version of a traditional folk song once a month and making it available for free online along with chords and background info on the songs and his connection to them. (The project has been spun off into three for-sale collections--one was nominated for a Grammy and another is an exhaustive four-CD compendium.) His latest studio album, Limited Edition (released in 2004) features several folk and blues songs electrified by his signature "jingle-jangle" style, plus seven new songs co-written with Camilla.

"I started it out of a genuine concern that the traditional side of folk was being neglected. Most people are singer-songwriters, because there' s more money in it," he says. "A lot of people don't even know it exists. They're brought up in a culture with other music and they've never even heard of it. So I'm just doing my part to keep it alive."

(continued below...)

McGuinn came up through the folk scene in Chicago before he joined a nascent band and helped re-shape pop music by scoring a number one hit with a rock and roll version of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” “I was a folkie before I was a rocker, I just kind of got into rock through the back door,” he recalls.

Though the conventional history of rock holds that The Beatles (John Lennon in particular) started incorporating atypical chord changes after hearing Dylan’s work, McGuinn traces the influence back to the Fab Four’s Liverpool roots.

“Liverpool is steeped in the folk tradition. If you listen to the old Beatles songs, they have sea chantey chord changes. It’s like The Beatles invented folk rock and they didn’t even know it. It was just part of their heritage, it was how they heard music.”

Nowadays, McGuinn tours with four instruments—a 12-string acoustic guitar, 12-string electric guitar, seven-string acoustic guitar, and banjo—so he can play whatever he’s in the mood for. He conjures up the “jingle-jangle” for Byrds favorites, tells some stories, dips into the Folk Den material—“whatever strikes me,” he explains.

“Camilla and I go around and play places and wander from town to town. I can see where some musicians would get tired of it when they go out with a band and a bus and trucks and it gets to be a grind. But if you're with your loved one, it's like a honeymoon.”

Though the conventional history of rock holds that The Beatles (John Lennon in particular) started incorporating atypical chord changes after hearing Dylan’s work, McGuinn traces the influence back to the Fab Four’s Liverpool roots.

“Liverpool is steeped in the folk tradition. If you listen to the old Beatles songs, they have sea chantey chord changes. It’s like The Beatles invented folk rock and they didn’t even know it. It was just part of their heritage, it was how they heard music.”

Nowadays, McGuinn tours with four instruments—a 12-string acoustic guitar, 12-string electric guitar, seven-string acoustic guitar, and banjo—so he can play whatever he’s in the mood for. He conjures up the “jingle-jangle” for Byrds favorites, tells some stories, dips into the Folk Den material—“whatever strikes me,” he explains.

“Camilla and I go around and play places and wander from town to town. I can see where some musicians would get tired of it when they go out with a band and a bus and trucks and it gets to be a grind. But if you're with your loved one, it's like a honeymoon.”